|

| Joseph Dreams of Home (Stravinsky's The Soldier's Tale) |

Seek Giacometti’s “The Palace at 4 a.m.” Go back two hours. See towers and curtain walls of matchsticks, marble, marbles, light, cloud at stasis. Walk in. The beggar queen is dreaming on her throne of words… You have arrived at the web home of Marly Youmans, maker of novels, poems, and stories, as well as the occasional fantasy. D. G. Myers: "A writer who has more resolutely stood her ground against the tide of literary fashion would be difficult to name."

Pages

- Home

- Seren of the Wildwood 2023

- Charis in the World of Wonders 2020

- The Book of the Red King 2019

- Maze of Blood 2015

- Glimmerglass 2014

- Thaliad 2012

- The Foliate Head 2012

- A Death at the White Camellia Orphanage 2012

- The Throne of Psyche 2011

- Val/Orson 2009

- Ingledove 2005

- Claire 2003

- The Curse of the Raven Mocker 2003

- The Wolf Pit 2001

- Catherwood 1996

- Little Jordan 1995

- Short stories and poems

- Honors, praise, etc.

- Events

SAFARI seems to no longer work

for comments...use another browser?

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Clive at Oriel Tefryn

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

Portals and awakenings

|

| Talking to Afghanistan, oil, 2013 |

If you're in the Otsego area of New York and have an interest in the region, the arts, or visual narrative, please come to an opening honoring Ashley Norwood Cooper at the Wilbur Mansion this Friday, 5-8 p.m. This Community Arts Network of Oneonta event hails the start of a solo show that features paintings from Ashley's new deployment series.

An interesting departure from Ashley's prior handling of paint, the mode of the paintings implicitly contrasts the smoothness of our world of screens and flattened-out images with a dramatic, built-up surface. These narrative pieces make ordinaryAmerican life strange--they are full of little portals (via held iPads and iPhones) to the other side of the world, and are themselves windows onto the daily duties and longings from the daily life of a mother and wife in middle-class America.

|

| Coming Home, oil, 2013 |

If you're in the area, please come!

* * *

A recommendation from Ashley--

Here's an essay Ashley suggested to me this morning, relating to many things we both find of interest. Jordan Wolfson discusses a lot of issues that our little IAM satellite group has talked about: the lack of "a stable purpose" of art in our era; the lack of correlation between achievement and regard when the artist's place is often established by how well he or she can interact with market forces; "secularization and fragmentation" as leading to a landscape where it's hard to achieve a place. Wolfson grapples with the question of how the arts function in our time, their "use and utility." He examines art's effort to awaken us--to take "raw material and somehow charge it with presence," "consciousness becoming aware of itself." Here are a few clips of note:

On the one hand, a painting is a flat two-dimensional object, with its surface texture and color shapes. On the other hand, a painting offers the possibility of a three-dimensional experience, the illusion of moving into space and discovering form. Stability and instability. Fact and imagination. Actual and fictive. It is this twin role, and its simultaneity, that gives painting such power. Real and unreal. Real and more real. Painting, through the coexistence of two seemingly opposite experiences, interwoven into an actual unity, may provide the receptive adult the possibility of moving from an experience of fragmentation into an experience of wholeness and integration, not only within oneself but with the world at large.Read the whole thing here.

Clement Greenberg got painting’s essence exactly wrong. It isn’t the stability of painting’s flatness—its “ineluctable flatness”; it is the inextricable unity of painting’s impossible flatness/fullness, stability/instability, stillness/movement. This is life.

Painting does have a necessary and ancient function; it isn’t to depict the world—it is to weave the world; or rather, it is to reveal and make visible the actual weave of the world, the weave that already exists.

I believe that what I am trying to describe here is actually an ancient way of looking at painting. Images carry power. It is only with the rise and development of our secular culture with its accompanying market economy that painting has found itself delegated to a luxury commodity that is devoid of any real use and value in our society beyond sophisticated decoration, investment and chic. This is not particularly the plight of painting—so much in our culture has been radically reduced to a flattened materialist, financial definition—the logical endpoint in the Story of Separation. But the act of painting carries much greater power than that. And we need to re-describe this activity, re-imagine it, in order to sharpen its power and focus; in order for painting to more fully participate and take its place in our global regeneration.

Wolfson is not alone in thinking about dead ends and regeneration, not just in painting but across the arts; it's something that a lot of us have been discussing. For one example, it's part of why Makoto Fujimura founded International Arts Movement "to promote conversation and meditations on culture, art, and humanity," and then Fujimura Institute, which describes itself as "defying fractured, fragmented modern perspectives, the Fujimura Institute encourages artists and thinkers to collaborate, cooperate and inspire their audiences to piece together a whole view of the world." It's why so many artists are turning away from what makes for worldly success in a blockbuster world and reaching back to old skills and tools in order to rethink and re-make an art for today.

Monday, April 28, 2014

Rounding up poetry--

Today

Lady Word of Mouth

features

Robbi Nester's anthology

from Nine Toes Press,

an imprint of

Lummox Press,

an imprint of

Lummox Press,

The Liberal Media Made Me Do It:

Poetic Responses to NPR and PBS Stories.

National Poetry Month,

2014.

Brand new news!

2014.

Brand new news!

from David Bayles and Ted Orland, Art and Fear

The artwork's potential is never higher than in that magic moment when the first brushstroke is applied, the first chord struck. But as the piece grows, technique and craft take over, and imagination becomes a less useful tool. A piece grows by becoming specific. The moment Herman Melville penned the opening line, "Call me Ishmael," one actual story--Moby Dick--began to separate itself from a multitude of imaginable others.

Last chances

Duende again! And poetry--

Gerry Cambridge and David Mason,

reading and talking in the Transatlantic Poetry on Air series

hosted by Robert Peake in London

and Jennifer Williams of the Scottish Poetry Library, Edinburgh.

(The duende discussion is at 59.10 if you haven't had enough of that subject

and want to hear that discussion before you listen to the poems.)

Hat tip to Patricia Wallace Jones and Paul Digby.

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Angel, muse, duende, and...

Black sounds, part 2.

Part one is here.

If we look at the sort of narratives that reach across the face of America, we find that Lorca's muse, angel, and duende are all missing. Perhaps this is no surprise. Studies have shown us that the majority of people don't engage much in written stories, the descendant of our most ancient around-the-fire way of engaging in explaining ourselves to ourselves. Many people who attend college no longer read books after they graduate. Of course, people gossip and tell anecdotes about those they know, although a recent article in The Atlantic suggested that conversation itself is under threat in a technological age. But for most, the art form where they encounter the told story is the movie. And the movie that reaches big screens in the hinterlands where I and many others live is the most popular movie of all, the one that is pushed by marketers, thrust on the populace, and that sells the most tickets.

For many decades now, we have lived in a world where marketers choose what most people read and watch. We have relinquished to them the power of creating our own culture by exploration and affirmation of what is true, good, and beautiful. This mode of establishing the direction of the main stream of culture has curious results.

If we take a look at The Hunger Games, the Twilight series, or some superhero saga like the latest Captain America: The Winter Soldier, we may believe that we find some clever, well-made movies of their kind--I'm not going to jump into an argument about individual films--but we also find an absence of muse, angel, and duende. Instead, there is a rejection of the powers of inspiration that come from Lorca's angel and muse, as well as an evasion of soulfulness. We find a strong insistence on the individual's ability and power to take control of his or her own life and wrest it away from the terrible structures made by human beings, as well as from the powers of death and God. Appointed deaths are ducked for the hero and heroine in The Hunger Games. Death dies for the central characters in the Twilight stories, and the risk to the soul no longer has any meaning. Vampires in Forks have little trouble with the burden of great, lonely age; they all have equal partners to console them for the endless cold. Captain America? In The Winter Soldier, Captain America shares with the old-fashioned vampire a burden of age that outlives mortal love. In all these cases, the one thing the protagonist must come to accept is friendship and the need to renew and make connections in order to survive.

Lorca's vision of the storyteller's trinity of possible inspiration--the angel who brings light and grace and thorn-crown of fire, the muse who may dictate and brings shapeliness and intellect to the work, and the earth spirit who burns in our blood and brings a baptism in dark water--is simply not needed or wanted in these Hollywood stories. They are ruled by another power entirely, the time ghost, the spirit of the age, the zeitgeist. And that is in great part why they are so popular. Matthew Arnold, coiner of the term, thought of the zeitgeist as a force that powered events, and from which we might want to take refuge.

The zeitgeist so evident in these and many other blockbuster movies is composed of interlocking parts like a toy transformer--technological, apocalyptic, and conspiratorial. A sense of overwhelming technological progress broods over the movies, and even invades places that could possibly be a wild refuge. Even what used to be raw and wild is internet-connected, and the powers of characters take on a technological edge. (Indeed, it's hard not to be frequently aware of the wonders of CGI when viewing most movies these days.) The wind of the zeitgeist blows through a landscape that is as violent and cruel as the killing grounds of the 20th century, but now the spirit of the age as seen in popular story is entangled in webs of conspiracy. Inside our filmic governments and powers are elaborate, subterranean schemes and initiatives that ordinary people are helpless to understand, even if we sense them or glimpse what we are allowed to see of them. The idea of widespread, powerful conspiracy rules the movie world, and tends toward the making (and unmaking) of apocalyptic events. Dread is the atmosphere we breathe. The human soul is in peril, liable to destruction or reduction.

In the face of such threats in movie land, our human (or once-human) characters do the thing that good capitalists do: they network. They make a counter-web to set against conspiracy and destruction. Our created blockbuster characters tend to give up all concern for the soul in their cornered efforts to survive the whelming technological and human plots against them. It's not so different from our daily lives, surrounded from waking with technological connections and pelted with disturbing news about the institutions intended to keep people safe. In our everyday life, we are bombarded with trivia and threats, distracted from depth and reflection.

With such a zeitgeist stirring the world, it's no wonder that a movie like Aronofsky's Noah headed straight for controversy; for once, a movie that pursues angel, muse, and duende has reached the hinterlands of America. The film turns its face away from technology and conspiracy and explores creation, obedience to divine will, and old apocalypse. Here is the creator God, making the universe in six periods of time before the time of rest, stirring a seed, raising a forest, and unlocking the extravagant fountains of the deep. Atheist he may be, but Aronofsky restores meaning to the word awesome. And here are we mortals, shown as the pluckers of the apple and in silhouette as slayers of Abel, a murderous tribe, generation after generation.

The lost drama of salvation returns in Noah, and the soul strives to grasp God and divine intention. In that realm, everything human beings do again matters and is of the very highest moment. The effort to understand God and do what is demanded can push a man to the teetery brink of madness. Oh, the movie has flaws, like some passages that seem pilfered from Peter Jackson's version of Middle Earth battles and from Jackson's mountains that step out as stone giants. But Aronofsky wrestles with the power of the angel and calls forcibly to the muse. He invokes the black sounds of duende and Lorca's baptism by dark water through the creation of a Noah of anguish and the fear of abandonment and death, through the man's passionate courting of heaven, and through the force of the blood tie of family that, in the end, saves the world a second time.

Angel, muse, duende: these are the three who battle the zeitgeist on our behalf, wielding their strange, piercing weapons. Perhaps they will yet bring us to fresher, truer, stronger stories, if we can only hand down the memory of what Melville called "deep diving," and the knowledge of how to read and see.

Part one is here.

|

| H. R. Giger, Birth Machine, 1910. Wikipedia + Creative Commons license |

For many decades now, we have lived in a world where marketers choose what most people read and watch. We have relinquished to them the power of creating our own culture by exploration and affirmation of what is true, good, and beautiful. This mode of establishing the direction of the main stream of culture has curious results.

If we take a look at The Hunger Games, the Twilight series, or some superhero saga like the latest Captain America: The Winter Soldier, we may believe that we find some clever, well-made movies of their kind--I'm not going to jump into an argument about individual films--but we also find an absence of muse, angel, and duende. Instead, there is a rejection of the powers of inspiration that come from Lorca's angel and muse, as well as an evasion of soulfulness. We find a strong insistence on the individual's ability and power to take control of his or her own life and wrest it away from the terrible structures made by human beings, as well as from the powers of death and God. Appointed deaths are ducked for the hero and heroine in The Hunger Games. Death dies for the central characters in the Twilight stories, and the risk to the soul no longer has any meaning. Vampires in Forks have little trouble with the burden of great, lonely age; they all have equal partners to console them for the endless cold. Captain America? In The Winter Soldier, Captain America shares with the old-fashioned vampire a burden of age that outlives mortal love. In all these cases, the one thing the protagonist must come to accept is friendship and the need to renew and make connections in order to survive.

Lorca's vision of the storyteller's trinity of possible inspiration--the angel who brings light and grace and thorn-crown of fire, the muse who may dictate and brings shapeliness and intellect to the work, and the earth spirit who burns in our blood and brings a baptism in dark water--is simply not needed or wanted in these Hollywood stories. They are ruled by another power entirely, the time ghost, the spirit of the age, the zeitgeist. And that is in great part why they are so popular. Matthew Arnold, coiner of the term, thought of the zeitgeist as a force that powered events, and from which we might want to take refuge.

The zeitgeist so evident in these and many other blockbuster movies is composed of interlocking parts like a toy transformer--technological, apocalyptic, and conspiratorial. A sense of overwhelming technological progress broods over the movies, and even invades places that could possibly be a wild refuge. Even what used to be raw and wild is internet-connected, and the powers of characters take on a technological edge. (Indeed, it's hard not to be frequently aware of the wonders of CGI when viewing most movies these days.) The wind of the zeitgeist blows through a landscape that is as violent and cruel as the killing grounds of the 20th century, but now the spirit of the age as seen in popular story is entangled in webs of conspiracy. Inside our filmic governments and powers are elaborate, subterranean schemes and initiatives that ordinary people are helpless to understand, even if we sense them or glimpse what we are allowed to see of them. The idea of widespread, powerful conspiracy rules the movie world, and tends toward the making (and unmaking) of apocalyptic events. Dread is the atmosphere we breathe. The human soul is in peril, liable to destruction or reduction.

In the face of such threats in movie land, our human (or once-human) characters do the thing that good capitalists do: they network. They make a counter-web to set against conspiracy and destruction. Our created blockbuster characters tend to give up all concern for the soul in their cornered efforts to survive the whelming technological and human plots against them. It's not so different from our daily lives, surrounded from waking with technological connections and pelted with disturbing news about the institutions intended to keep people safe. In our everyday life, we are bombarded with trivia and threats, distracted from depth and reflection.

|

| Bernini, the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, c. 1660. Apse of St. Peter's Basilica. Wikipedia Commons, public domain. |

The lost drama of salvation returns in Noah, and the soul strives to grasp God and divine intention. In that realm, everything human beings do again matters and is of the very highest moment. The effort to understand God and do what is demanded can push a man to the teetery brink of madness. Oh, the movie has flaws, like some passages that seem pilfered from Peter Jackson's version of Middle Earth battles and from Jackson's mountains that step out as stone giants. But Aronofsky wrestles with the power of the angel and calls forcibly to the muse. He invokes the black sounds of duende and Lorca's baptism by dark water through the creation of a Noah of anguish and the fear of abandonment and death, through the man's passionate courting of heaven, and through the force of the blood tie of family that, in the end, saves the world a second time.

Angel, muse, duende: these are the three who battle the zeitgeist on our behalf, wielding their strange, piercing weapons. Perhaps they will yet bring us to fresher, truer, stronger stories, if we can only hand down the memory of what Melville called "deep diving," and the knowledge of how to read and see.

|

| "Muses Sarcophagus," The Louvre Roman, 2nd century A. D. Public domain, via Wikipedia |

Friday, April 25, 2014

Black sounds: 5 readings

|

| Henri Rousseau, La Muse Inspirant le poète, 1909. Guillaume Apollinaire with painter Marie Laurencin. via Wikipedia, public domain. |

from Federico Garcia Lorca, "Theory and Play of the Duende"(1933)

translation by A. S. Kline - read the full version here

For every man, every artist called Nietzsche or Cézanne, every step that he climbs in the tower of his perfection is at the expense of the struggle that he undergoes with his duende, not with an angel, as is often said, nor with his Muse. This is a precise and fundamental distinction at the root of their work.

The angel guides and grants, like St. Raphael: defends and spares, like St. Michael: proclaims and forewarns, like St. Gabriel.

The angel dazzles, but flies over a man’s head, high above, shedding its grace, and the man realises his work, or his charm, or his dance effortlessly. The angel on the road to Damascus, and that which entered through the cracks in the little balcony at Assisi, or the one that followed in Heinrich Suso’s footsteps, create order, and there is no way to oppose their light, since they beat their wings of steel in an atmosphere of predestination.

The Muse dictates, and occasionally prompts. She can do relatively little since she’s distant and so tired (I’ve seen her twice) that you’d think her heart half marble. Muse poets hear voices and don’t know where they’re from, but they’re from the Muse who inspires them and sometimes makes her meal of them, as in the case of Apollinaire, a great poet destroyed by the terrifying Muse, next to whom the divine angelic Rousseau once painted him.

The Muse stirs the intellect, bringing a landscape of columns and an illusory taste of laurel, and intellect is often poetry’s enemy, since it limits too much, since it lifts the poet into the bondage of aristocratic fineness, where he forgets that he might be eaten, suddenly, by ants, or that a huge arsenical lobster might fall on his head – things against which the Muses who inhabit monocles, or the roses of lukewarm lacquer in a tiny salon, have no power.

Angel and Muse come from outside us: the angel brings light, the Muse form (Hesiod learnt from her). Golden bread or fold of tunic, it is her norm that the poet receives in his laurel grove. While the duende has to be roused from the furthest habitations of the blood.

Reject the angel, and give the Muse a kick, and forget our fear of the scent of violets that eighteenth century poetry breathes out, and of the great telescope in whose lenses the Muse, made ill by limitation, sleeps.

The true struggle is with the duende.

The roads where one searches for God are known, whether by the barbaric way of the hermit or the subtle one of the mystic: with a tower, like St. Teresa, or by the three paths of St. John of the Cross. And though we may have to cry out, in Isaiah’s voice: Truly you are a hidden God,’ finally, in the end, God sends his primal thorns of fire to those who seek Him.

Seeking the duende, there is neither map nor discipline. We only know it burns the blood like powdered glass, that it exhausts, rejects all the sweet geometry we understand, that it shatters styles and makes Goya, master of the greys, silvers and pinks of the finest English art, paint with his knees and fists in terrible bitumen blacks, or strips Mossèn Cinto Verdaguer stark naked in the cold of the Pyrenees, or sends Jorge Manrique to wait for death in the wastes of Ocaña, or clothes Rimbaud’s delicate body in a saltimbanque’s costume, or gives the Comte de Lautréamont the eyes of a dead fish, at dawn, on the boulevard.

The great artists of Southern Spain, Gypsy or flamenco, singers dancers, musicians, know that emotion is impossible without the arrival of the duende. They might deceive people into thinking they can communicate the sense of duende without possessing it, as authors, painters, and literary fashion-makers deceive us every day, without possessing duende: but we only have to attend a little, and not be full of indifference, to discover the fraud, and chase off that clumsy artifice.

from Edward Hirsch, A Poet's Glossary (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014)

Lorca

uses the word duende in a special Andalusian sense as a term for the obscure power and penetrating inspiraton of art. He describes it, quoting Goethe on Paganini as "a mysterious power which everyone senses and no philosopher explains." For him, the concept of duende, which could never be entirely pinned down or rationalized was associated with the spirit of earth, with visible anguish, irrational desire, demonic enthusiasm, and a fascination with death...David Bowman Jr. for Addie Zerman

Duende, then means something like artistic inspiration in the presence of death. It has an element of mortal panic and fear, the power of wild abandonment. It speaks to an art that touches and transfigures death, both wooing and evading it...

Duende exists for readers and audiences as well as for writers and performers. Lorca states: 'The magical property of a poem is to remain possessed by duende that can baptize in dark water all who look at it, for with duende it is easier to love and understand, and one can be sure of being loved and understood."

To paraphrase “Play and Theory of the Duende,” García Lorca said that great art depends on connection with a nation’s soil, a vivid awareness of death, and an acknowledgment of the limitations of reason.

Lorca believed that what makes a poem powerful comes from a specific orientation, one that springs from suffering and from the earth, one that privileges imagination to lead us beyond mere reason.

Nick Cave on duende and song at everything2

The love song must resonate with the susurration of sorrow, the tintinnabulation of grief. The writer who refuses to explore the darker regions of the heart will never be able to write convincingly about the wonder, the magic and the joy of love for just as goodness cannot be trusted unless it has breathed the same air as evil - the enduring metaphor of Christ crucified between two criminals comes to mind here - so within the fabric of the love song, within its melody, its lyric, one must sense an acknowledgement of its capacity for suffering.

Tracy K. Smith on duende at poets.org

I love this concept of duende because it supposes that our poems are not things we create in order that a reader might be pleased or impressed (or, if you will, delighted or instructed); we write poems in order to engage in the perilous yet necessary struggle to inhabit ourselves—our real selves, the ones we barely recognize—more completely. It is then that the duende beckons, promising to impart "something newly created, like a miracle," then it winks inscrutably and begins its game of feint and dodge, lunge and parry, goad and shirk; turning its back, nearly disappearing altogether, then materializing again with a bear-hug that drops you to the ground and knocks your wind out. You’ll get your miracle, but only if you can decipher the music of the battle, only if you’re willing to take risk after risk. Only, in other words, if you survive the effort. For a poet, this kind of survival is tantamount to walking, word by word, onto a ledge of your own making. You must use the tools you brought with you, but in decidedly different and dangerous ways.

If all of this is true, and I believe it is, this struggle is not merely to write well-crafted and surprising poems so much as to survive in two worlds at once: the world we see (the one made of people, and weather, and hard fact) that, for all of its wonders and disappointments, has driven us to the page in the first place; and the world beyond or within this one that, glimpse after glimpse, we attempt to decipher and confirm. Survival in the former is predicated on balance, perspective, rehearsal, breadth of knowledge and experience. It’s possible to get by as a poet with those things alone. Many do. A healthy ego doesn’t hurt. But for someone fully convinced of the duende, it’s the latter world that matters more. The world where madness and abandon often trump reason, and where skill is only useful to the extent that it adds courage and agility to your intuition.

Practically speaking, this dual reality translates into something very simple for the poet: talent only goes so far. Talent only leads up to the door where the real reason for writing—or continuing to write—resides. Talent will get you there and raise your hand to the knocker. After that, what pulls you inside and keeps you alive can only be need. The need for answers to unformed questions. The need for an echo back from the most distant reaches of the self. The need to stop time, to understand the undecipherable, to believe in a What or a Whom or a How. The need for a kind of magic—Lorca’s "miracle."

Thursday, April 24, 2014

Memory Palace and form-in-poetry rant--

|

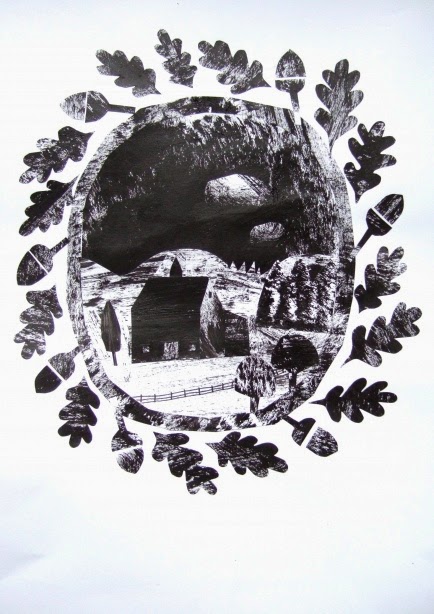

| rear cover image by Clive Hicks-Jenkins, The Foliate Head |

Thanks to my excessively courteous Southern upbringing and the disapproving glances of my ancestors, I eventually turned out to be a person who--once I'd grown up, which took me about 30 years--is probably a little too empathetic and who hates to hurt people's feelings and feels boiled in oil for weeks afterward if I accidentally do so. So I have to say that I am very glad that Nina Kang has such very different opinions from me because she has given me the chance (thank you!) to realize what my own are.

On the other hand, I feel guilty that her well-reasoned opinions are not mine, not in the least. I find my thoughts divergent in almost every respect from hers as displayed in "The Lost Art of Memorization" (Hat tip to Prufrock News.) I expect she stands with the majority, so perhaps my disloyalty won't bother her much if she ever wanders this way.

Memory Palace

I suspect Nina Kang started her attempt to memorize a poem without researching how people have memorized poems in the past. She failed at memorizing a poem, it seems, because she didn't think about those things and develop additional tricks that worked for her. It's not that hard if you use some of the tools developed over the centuries. And I'm sure Nina has a much younger brain than mine, which is no doubt shrinking on its way toward brain-oblivion. Here is a post where I talk about my memory palace plan and how I will memorize. Here is a list of my posts about memorizing poems.

I definitely don't agree that "memorization . . . is something our culture has largely evolved beyond." (And I expect that she doesn't either, really, ending her article with a moment of recitation that works on her like a spell.) If you read a poem, you lay some claim to it. But if you memorize a poem and it follows you over months and years, it becomes yours in an entirely different way. At surprising moments it will rise up in the mind, oddly congruent or oddly at odds with what goes on around you. It will console and surprise in a way that no poem on a page back at your house or on your laptop can do. You will also meet the poem more often and so understand in a more complicated way over time.

Reciting hurts poetry?

The purest, most effervescent distillation of hogwash-and-seltzer appears in these words against memorization:

In fact many argue today that recitation actively hurts poetry. Ron Silliman complains: “To recite a poem, one is required to have the whole of it in mind, to be ever vigilant as to one’s position—the way an actor has to be on stage—with all of its past and its future right at the surface of awareness. One is perpetually other than present with the text at hand.”If you stay with a poem, if you repeat it over time and learn it thoroughly, this is not in the least what the mind experiences. Why should we take the word of people opposed to memorization? I see such sources as a real difficulty with this argument. Because I have a different experience memorizing poems. Eventually the mind knows the words so well that the poem can flood through the mind and body, and it is often experienced in a far more ravishing way than when read on the page. Sure, I find that at first and perhaps for a while, a difficult poem may have to be considered more carefully. When I hit "Sorrow's springs are the same," I still sometimes have to remember my clue to the knotty next: "Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed." (My clue is the "mouth" of a "spring.") Eventually I'll never need to jump to a clue and back. But when I have to use a clue, I go through the poem a second time, and then don't need the clue. It is now my poem, and I, like Thoreau and the apple fields, own it in a better way than others who may own field or book but have not taken its essence for their own.

Rather than being "other than present," I slide through the words like a mermaid through a sluice of current in the sea. I swim in them, and they are in my mind and mouth and all that I see. You know, I like that idea a great deal better than Silliman's "ideal of poetic 'mindfulness' where the reader can live in a sort of eternal present as the words wash over her." Why have a wave when you can have the ocean? "Mindfulness" is still fashionably hip, but in the case of poetry I prefer total immersion over a wash of mindfulness, and wish that I knew many more poems by heart than I do. Well, it's one of my 2014 projects, so we'll see what happens by year's end.

Suppress amateur reciters?

Ah, dear, human nature rising up again with all its passion! I do like to be kind and sympathetic, but I am afraid that I hate this attempt to suppress "amateur reciters."

Further damage can be dealt to a poem by amateur reciters (as opposed to actors) who may end up delivering the line in a singsong fashion, coercing the poetic line into a strict meter which may not be entirely natural. Thus a blank verse line from Hamlet, “Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,” when recited, can take an exaggeratedly ta-TUM, ta-TUM quality: “Thus CON-science DOES make COW-ards OF us ALL.” The rhythm of that delivery compromises the meaning of the text by putting an unnatural stress on the words “does” and “of,” and causing us to mentally de-emphasize the more important words “make” and “us.” In fact, the whole question of meaning can recede into the background, since rote memorization can and often does accompany a lack of understanding of the poem’s actual meaning.This idea is absurd. Let's take an example of children (the biggest amateurs of all.) When my daughter's fifth-grade class memorized poems (including pieces from Shakespeare's plays and poems by Kathleen Raine and Charles Causley and many more) that I had chosen for them, they were quite capable of delivering poems with force and gusto and without a hint of singsong. They sounded wonderful. They were proud of knowing their chosen poems, and they knew them inside out and had opinions about how they sounded and what they were about. Years later, my daughter could still recite Puck's song from MND and Raine's "Spell of Creation." Maybe she still can... I'll have to ask the young student of film and graphic novel some time. Take note of this: there was no exaggerated rhythm. There was no lack of understanding. Meaning did not wander off from the words like some unfortunate divided Siamese twin, or like a soul chopped from the body. Those children of ten and eleven felt words in their bones. So can you, if you take the trouble to memorize.

ta-TUM or the Castle of Indolence?

Kang sides with the idea that poets dislike meter and so write poems that are hard to memorize: "Unsurprisingly, then, many of today’s prominent poets seem to be writing poems that actively resist memorization." This assertion relates to the nonsensical idea that memorizers will go ta-TUM ta-TUM if they memorize metrical poetry. (My experience is that the more they memorize and recite, the less likely this is to occur.) The fact is that many of "today's...poets" write poems that will make the reader come a cropper when they try to memorize because it is very difficult to memorize what is sometimes--not always, of course, but it's true of all poets that most of our poems are not our best poems--slack prose broken into lines.

The modernists had formal verse in their bones and were still metrically dramatic and aware of the richness of sound when writing "free" verse; they broke their lines and rhythms against something known. Today's young writers are generations past that fruitful sundering. Too often new poets come of age in Tom Disch's Castle of Indolence (a term and title he borrowed from earlier poet James Thomson), not knowing their ancient, essential tools. You can't shatter form with power if you don't know form in the first place.

Bowdlerization as argument

Kang proceeds to break up some Ashbery lines, change words to be more archaic, and add rhyme and anapests to show what a bad decision formal verse would be; that's nonsensical, as all she does is bowdlerize some lines and then declare them some kind of proof of the weakness of a form that would allow better memorization. She finds the lines catchier but not as good and says, "But it also seems just bad."

Well, of course it's "just bad" (if not completely terrible) because it's not a made poem that came out of somebody's intense, charged play with words but a bowdlerized pseudo-poem! And those roly-poly anapests in the first line that she added have a built-in humorous swing that's wholly inappropriate to the subject. (Side note: The final line, “Into the chamber behind the thought,” does not "end with two dactyls and two iambs." "Into the / chamber / behind / the thought" can be read as dactyl, trochee, and two iambs.)

She does, however, prove that bowdlerizing an existing poem is a bad idea.

After giving us a bowdlerized non-poem to sample for its rhyme and meter, she declares that "we’ve developed a collective allergy to the 'ta-TUM ta-ta-TUM' of the strictly metered line; it makes us think of nursery rhymes and doggerel." Nina Kang, I confess that your bowdlerized non-poem does make me think of doggerel, as you intended it to do.

Another confession

I have something else to confess. I used to write free verse. All the time. I still do, now and then, when I feel as chained as Prometheus on the rock and charge at the sky. That's because the desire to break free now happens only when I've been writing a lot formal poems.

You say we've developed an allergy to the rhythm embodied in your bowdlerized poem. But you know what happened to me?

I got bored.

"Heavy bored," as Berryman's narrator said, long ago, in The Dream Songs.

I don't mind a bit or a whit that others (including Nina) did not become bored with their own free verse, but I tumbled into love with intricate sound and the drama of meter. It's just so darn much more interesting and powerful and fun to me. I'm not saying I can't enjoy any free verse; I'm saying that for me formal poetry became "the flashing & bursting tree!"

Your tree is something else? Fine. There's room. It's a big forest.

Tradition and moving forward

Sometimes, when an art form becomes fey and enervated, the only way forward is through the tradition. For me, my era just happens to be one of those times. Whether you believe that idea or not, the world contains many modes and many paths, including ones that point forward through the wilderness of the metrical past.

Access to power and larger life

Nina Kang says, "Unfortunately, that strict meter we dislike was a pretty valuable mnemonic tool." Yes, it was. And she says, "memorizing free verse poetry often feels like solving a crossword with only half the clues." She's right about those things.

But what she doesn't seem aware of is that the missing "clues" were a lot more than "mnemonic tools." They were access to power for those who could grasp and wield it, and also for many more now-forgotten writers who rejoiced in the attempt to dance the great dance of art with rhythm and song. Most writers, you know, are forgotten in time--most people are forgotten, along with any joy they pursued. But they pursued their joys with vigor in their time, I hope, and lived bigger lives because of them.

In fact, even now some of us are just not in love with the "intentionally haphazard text" and "deliberate awkwardness" of "today's prominent" (or not-prominent) poets but with the idea of combining forms with a voice that sings and speaks in the accents of our own time. And that's a greater, mightier, riskier challenge that any memorizing or writing of the "deliberately awkward" and "haphazard."

Knowing your tools

To any young poet, I would say that no matter what sort of poetry you want to write, you must know your tools. Any artisan should be known and judged first by a basic mastery of his or her tools. Be known by no less. If you don't know your tools, you're nothing but a naked Empress of a performance artist--just another in a rather long, dull line of "artists" thrusting or pulling or spitting or unreeling something or other out of one or another artifice-orifice--a naked human being plopping paint-filled "eggs" out of your vagina and calling it art. Know your tools, no matter what and how you want to make, no matter how you want to stand in relation to the tradition from which you spring... Know that tradition.

Then take joy in creation.

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

"A fantastic in poetry that makes sense"

|

| Clive Hicks-Jenkins vignette for Thaliad |

Despite this, soft surrealism—that is, a little incoherence there, an out of place violent or sexual image there (no one tries to actually use automatism)—is still relatively popular today. It makes a poem look edgy, in-the-know, and it has a nice leftist pedigree. The problem is that this soft surrealism can hide incompetence and often adds nothing to a poem, other than the above stylish marking. (Examples—almost all published this month—can be found here, here, here, here, and here.)

Stephen Burt has written against this soft surrealism, which he calls “elliptical poetry,” and has suggested that a renewed focus on objects in poetry—on “well-made, attentive, unornamented things”—might (and should) replace the “slippery, digressive, polyvocalic,…overlapping, colorful fragments” of a still fashionable soft surrealism.

I would propose a different route. Getting rid of incoherence, meaningless images, fragmented syntax, and so forth, could open a much needed opportunity for a fantastic in poetry that makes sense. Too long has the fantastic been wedded to Breton’s watered-down automatism, and breaking definitively free from it might open the field for more poems like Marly Youmans’s Thaliad or Joe Fletcher’s Sleigh Ride. And that would be a very good thing.

There are some interesting responses... And I don't know Joe Fletcher. I'll have to remedy that gap!

The Songbird Guns

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come

It's National Poetry Month. For all you prompt-loving poets and writers out there in the known universe, try the inspiration of Christie's Aurel Bacs and the paradox of these works that combine the skills of a jeweler and an automaton maker with the look of pistols. These little "swords-into-ploughshares" items are among the strangest valuable objects ever made . . . and the most expensive joke guns ever.

My husband points out that these are a matched pair--dueling pistols, then, as if for a mock duel. No wonder they were made for a non-Western market, then, as the subject would have been far too serious in the West at that time. It took the West a many years to get to “Your mother was a hamster, and your father smelt of elderberries!” (Thank you, Monty Python, for taking us so far.)

I am also reminded of my husband's description of songbird duels in Hanoi. I would have liked to wander that street of birds. Dueling, birds, and Asia: it fits so neatly!

If you're not a poet or writer, the songbird guns are still remarkable. Take a look if you need a little absurd, marvelous birdsong in the morning.

Here is the description from Christie's, intricate with detail:

Rectangular gilt brass movements, chain fusées, circular bellows, double-barreled pistol-shaped cases, the grips with translucent scarlet enamel over engine-turned background, set with one pearl and diamond-set and one diamond-set rosette, split pearl-set lower edges, the upper edges decorated with black enamel and pearl-set laurel wreaths, the grips' reverses embellished with gold and black enamel pattern and pearl-set scroll and foliage motifs, both pistols centred by split-pearl framed gold plates chased with a lion on one side and a stag on the reverse, the top edges set with half pearls, gold matted and engraved hammers, the heads of the flint vises engraved with lion's heads, gold vise nuts terminated with diamonds, agate flints, gold pan covers with polished interiors, the outsides engraved with acanthus leaves, their springs terminating with diamonds, opening under the right pan covers for sound, the blue enamelled double barrels decorated with paillonné and laurel foliage simulating damascene works, three barrel-like ramrod pipes to the undersides, the ramrods containing the keys for the bird movements, the birds released by the percussion of the hammers when the triggers are depressed, the front covers opening and revealing painted varicoloured enamel bouquets of flowers over turquoise enamel, the birds set with realistically multicoloured feathers, lifting to the top of the barrels, turning, flapping their wings, opening the beaks and moving their tails, in time to a lifelike imitated bird song, when the song has finished the birds will automatically retreat inside the pistols and the covers will close.Attributed to Frères Rochat.

Circa 1820, for the Chinese market.

* * *

I am continually bemused by which posts or tweets receive comments. There must be a secret to it that I do not always grasp. Sometimes, though, it's easy: none on this one, but quite a few amusing ones on another posted later the same day at facebook--on an article about a young, naked performance artist who "paints" by pushing "eggs" full of paint out of her vagina." "Anywhere but an art gathering, this would be regarded as a satire on modern cultural emptiness."

Monday, April 21, 2014

Springtime book news roundup

|

| Clive Hicks-Jenkins, interior vignette for Glimmerglass |

POETRY SALE

Phoenicia Publishing news: they are having a spring sale in honor of National Poetry Month. I posted about this earlier, or go straight to Phoenicia. Please share a link and information. Small presses need your help to find new audience. Yes, you!

NEW ANTHOLOGY

Mary Meriam's Irresistible Sonnets is out from Headmistress Press, and fits the title--many wonderful poems and much variety. Here is the anthology as featured at Lady Word of Mouth. Please support the book by spreading the word and/or by a purchase.

RT

Thanks to those who commented on RT's poetry questions here and at facebook--take a look if you haven't seen them, and feel free to toss in your two cents.

NPM BOOK GIVEAWAY

The Big Poetry Giveaway is on through the end of the month; if you want to toss your name in the hat for one of my books (and a second book by another writer), leave a note in the comments here.

TOO DRATTED MEEK

I expect to declare the patreon experiment a failure (same three as the first day!) fairly soon, as I don't have the right personality to drum up supporters. Perhaps I thought the whole thing would work by magic, but I am confronted with my own refusal to bang the drum. I suppose that's a good thing to realize, though why I didn't know it clearly enough already is a mystery.

THE POWER OF EW

Ever since the Entertainment Weekly piece that included my novel Catherwood, out-of-print copies of that book have been steadily selling at various used-book websites, and doing much better than any single one of my in-print books from the looks of things. I'd better get working on an ebook and paperback for that one. FYI, my in-print books are the recent A Death at the White Camellia Orphanage, Thaliad, The Foliate Head, and The Throne of Psyche (see tabs above for information and links.)

GLIMMERGLASS

is the Mercer pipeline and will be out in fall...

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Resurrection light

|

| This oil by Bramantino (1455-1536) portrays an unearthly Jesus who has passed through agony and the realm of death. He is the man who bears the marks of suffering on body and in face, and is also the Christ of the Trinity. Silvery, transfigured shroud, moon-luminous skin, and sorrowful eyes--the eyes have seen all. Below the right hand is the abyss of death. Behind, a ship's mast reminds the viewer of Golgotha's cross and also of imminent departure. In the sky is a moon, which I fancy looks rather like the eucharistic host, a reminder that the resurrection of Christ remains in the mortal world after the Ascension. Via Wikipedia, public domain. |

Friday, April 18, 2014

"Angelic brother"

|

| A bit of work from the wondrous hand of Fra Angelico (1395-1455) for Good Friday. Detail from a crucifixion including both fall and redemption, the blood of Christ beginning to stream onto the skull of Adam. Via Wikipedia, public domain. |

Thursday, April 17, 2014

RT's questions about poetry

|

| Clive Hicks-Jenkins. Rear cover image for my collection The Foliate Head. UK: Stanza. |

Are there now more poets than readers?

Perhaps. Considering the efforts of Modernism to eradicate readers, I’m always surprised to find people who like poetry. In my experience, non-poets tend to like older poetry, and certainly it’s easier to find good poems in the past, where the weeds have been weeded, and the slight have been slighted.

Earlier on this blog I mentioned a conversation I had with an editor at a house that dropped its line of poetry because they had not broken the 300-mark on copies in recent years. That gives you some idea. I’ve also talked to editors with a poetry book or two that hadn’t broken the 50-mark. So it’s not an easy business, if you can indeed call it a business, this selling of poetry books. “Gift economy” was invented for such work.

By the way, I think a stranger problem is that there are many people writing poetry who are not great readers of poetry. There are many who are not conversant with the major poets of the past. I find this . . . astonishing.

I’m not sure how I became a reader of poetry at a very young age, but part of it must have been having parents who read poetry and fiction and bought me anthologies and books. I’m not so sure how one learns an early love without such parents.

A great many poets are part of the academic system, and this contributes to the sense that poets are increasing, readers decreasing. Plenty of people have talked about the multiplication of writing programs, and how they give birth to new creative writing professors and programs. Plenty of people have talked about how English literature departments have destroyed their once-healthy programs by an over-reliance on theory and “studies” concentrations. So on one hand, we increase poets and on the other, we decrease readers.

Unfortunately, this change enforces the idea that poets are “other” and do not belong to the daily world. And that idea enforces the idea that poetry is not for the daily world.

A poem can become a thing it should not be in an academic context. In the case of an academic who is a writer, each work is a potential “credit” on the yearly report that may help bring about a promotion or win merit pay (or inequity pay.) A poem becomes a kind of tick-mark in a box. It's suddenly useful in a practical way. The goal of poetry shifts. I don’t like that idea.

In addition, while it is lovely to be around young people, one’s main reading may become the unrevised work of college writers. It’s very easy to misjudge one’s own work and gifts in that context.

How do poets deal with that possible reality?

|

| Clive Hicks-Jenkins, interior page from my long poem Thaliad, now on National Poetry Month sale at Phoenicia Publishing |

However, the increasing reliance on adjuncts may alter the equation. Perhaps, though, there will always be those willing to be underpaid as the price of staying in such a world.

I do know poets who were not part of such a community (or else were fringe members) who did not manage well—who felt too keenly the lack of audience, the lack of notice for their work. And I’ve seen it ruin lives or decades of lives. No matter how fine the poet, he or she must be very strong to be a poet outside the supportive world of academia. He or she will lack the in-person connections that assist with publications and summer gigs, the aid to attend conferences, and much more. (Full disclosure: I walked away from achieved tenure and promotion and salary because I felt that the academy was the wrong place for me as a writer. And I do feel that I lost “a system,” and that has hurt my work in terms of marketing. But I do not regret the decision.)

Despite the frequency of open readings or poetry slams in cities, almost every poet alive has to at some point deal with the often-discussed idea of a diminished audience and diminished attention. Like any other form of writing, a poem is not quite complete if left unread.

And perhaps nearly every serious poet could take advice from Yeats’s address to one “whose work has come to nothing” because nearly every poet (aside from Billy Collins and Mary Oliver and a few more) is aware that readership that once was an ark is now little better than a village ferry over a stream. Worldly success will not come to most poets. A maker to “honor bred,” Yeats says, is “Bred to a harder thing than Triumph.” In the end, he advocates a turn toward passionate creation, which must be its own satisfaction: “Be secret and exult, / Because of all things known / That is most difficult.”

What are the best ways to reach new readers of poetry (if that is even possible in our 140-character Twitter world)?

Help. Start discriminating what is fine from what is dross. It’s become a non-no to say that some work is better than other work. As a result, we’re drowning in dross, while our era tells us that we need to include everybody. When it comes to high culture, full inclusion is a recipe for dismantling and destroying and losing the bright needle in the haystack.

If you can, guide others. Share what is true, beautiful, and strong.

Teach good taste to children. We stopped doing that more than a century ago, and our culture feels the effects.

Teachers and politicians should quit trying to make poetry useful.

A good many poets should stop publishing poems that are little more than broken prose—that lack force, music, and subject matter. The first free verse writers knew the sources of power in form. Poets should know formal poems, no matter what they write. (Here we are back to the idea that some poets don’t know the literary history of their own language.)

Review ‘zines. We have a huge proliferation of online ‘zines. This trend is good and bad, of course. It’s very hard to sift so much work. But I suppose it may “reach new readers.”

Sites that aggregate poetry of the past may be helpful. I don’t really know. I’ve seen an awful lot of nonsense about good poems as a result, though.

Nor do I know if clever poets active on twitter increase their audience. There are people on who write poems as twitter lines, later presenting them as whole poems. I have several in a twitter sub-group.

I’m not crazy about the way poetry is taught in schools, though I believe the situation is improving. I think we need more memorization and less analysis. Also, we really need children to encounter wonderful poems from the past that sing and are still alive. We don’t need to give them only “children’s poems.” (But if we do, I hope we give them some Charles Causley!)

Teachers need to remember that the reading of a poem is not an encounter between a cadaver and a medical student with a scalpel. Reading a first-rate poem should be an experience.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Phoenicia in the spring: NPM sale

From Phoenicia Publishing:

From Phoenicia Publishing:In honor of National Poetry Month, we've put ALL our poetry titles on sale at 20% off. The sale applies only to orders placed directly through our online store (no Amazon orders, sorry); at check-out, please enter code Q6C5Z6HY and the discount will be applied. Thanks for your support of poetry, poets, and independent publishing!

Phoenicia catalogue here, including poetry by Rachel Barenblat, Dave Bonta, Dick Jones, Ren Powell, etc.

* * *

Thaliad in Favorite Books of 2012, Books and Culture

In THALIAD, Marly Youmans has written a powerful and beautiful saga of seven children who escape a fiery apocalypse----though "written" is hardly the word to use, as this extraordinary account seems rather "channeled" or dreamed or imparted in a vision, told in heroic poetry of the highest calibre. Amazing, mesmerizing, filled with pithy wisdom, THALIAD is a work of genius which also seems particularly relevant to our own time. --novelist Lee Smith

For more comments, review clips, etc., go here.

Feel free to answer R. T.'s questions in the comments while I go to fetch-and-ferry a child... Back later with thoughts!

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

Hodgepodgery

|

| "Madison," WCU, circa 1904. |

What hometown fun! Thanks to undergraduate Amelia Holmes for the article on me in Nomad: The Quasquicentennial Edition (Western Carolina University), written for Dr. Kinser's senior seminar course. "The students wrote about topics related to Western Carolina University, highlighting the university and its faculty over the course of 125 years." My father was professor of analytical chemistry, and my mother head of serials at Hunter Library, WCU.

Rereading. Christopher Beha on "Holy crap":

So here’s my main point: books that one doesn’t know how to read, books that challenge our ideas about what fiction is supposed to be doing, are more interesting to talk and think about. And at least when it comes to fiction, these are the books that I want professional critics weighing in on, so these are the books that I want the TBR to cover. Unfortunately, the phrase we most frequently use to describe such books is the same phrase we use to describe members in good standing of the conventional genre called “literary fiction.” This is one reason I don’t really like the phrase “literary fiction.” It is also one reason I don’t like thinking about books as members of genres at all. Instead I like to think about individual books. If I have to think about genres I suppose it could be said that the genre of fiction I find most interesting to talk and write and read about—the one I think the TBR should be reviewing—is the genre that has the genre specification “does not conform to any genre specifications.” For our purposes I would call this genre “Holy Crap fiction.” In case I haven’t made this clear, lots of Holy Crap fiction isn’t all that good. Certainly lots of it is objectively worse than the average competent genre novel. But even bad Holy Crap fiction is far more interesting to talk about and read about than a competent genre novel, because it requires making sense of. A corollary to this is that there is no such thing as a merely competent Holy Crap novel.

Launch day

Gary Dietz's book of heartfelt, real-life narratives about fathers and disabled children has its launch day today. I've updated the page on Lady Word of Mouth to include more purchasing links and the book's facebook page--please visit and like.

More thoughts on patreon

10 p.m. Monday: At the end of 48 hours on patreon, I have three patrons... and am still pondering whether this is: a.) desirable; b.) useful; c.) all-around okay; or something I can do, since I am somewhat allergic to vigorous horn-tooting. Anyway, tonight there are three pieces up, all free. Nevertheless, I could dither over my opinion if I had time. However, I don't right now. Maybe after tonight's eclipse, if I don't crash. Should peak about 3:00 here. Yawn. However, it seems to be . . . raining.

|

| Art for Glimmerglass by Clive Hicks-Jenkins |

The galleys are done. I proofed and made five little tweaks. And that's THE END of that. Next time I'll see a .pdf with Clive's art in place, so that will be exciting. The design for chapter openers looked lovely. Then will come lovely new books.

Great poetry giveaway

We're about halfway through the time for the giveaway. One lucky person will receive a couple of books...

At Salon: David Foster Wallace was right: Irony is ruining our culture

But David Foster Wallace predicted a hopeful turn. He could see a new wave of artistic rebels who “might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels… who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles… Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue.” Yet Wallace was tentative and self-conscious in describing these rebels of sincerity. He suspected they would be called out as “backward, quaint, naïve, anachronistic.” He didn’t know if their mission would succeed, but he knew real rebels risked disapproval. As far as he could tell, the next wave of great artists would dare to cut against the prevailing tone of cynicism and irony, risking “sentimentality,” “overcredulity” and “softness.”

Wallace called for art that redeems rather than simply ridicules, but he didn’t look widely enough. Mostly, he fixed his gaze within a limited tradition of white, male novelists. Indeed, no matter how cynical and nihilistic the times, we have always had artists who make work that invokes meaning, hope and mystery. But they might not have been the heirs to Thomas Pynchon or Don Delillo. So, to be more nuanced about what’s at stake: In the present moment, where does art rise above ironic ridicule and aspire to greatness, in terms of challenging convention and elevating the human spirit? Where does art build on the best of human creation and also open possibilities for the future? What does inspired art-making look like? --Matt Ashby and Brendan Carroll

Dear Salon,

Look harder. A lot of us out here in the wilderness have been making art out of words and paint and more, setting ourselves against the grain of the times. Plenty of us have devoted our lives to making a kind of art that can soar up above nihilism and despair and irony--making "art that redeems" in opposition to what is most lauded and supported by the system that tells people what art to see and read. Put on your glasses. Those who have eyes to see, let them see.

So touching...

I love this little article about writer Hugh Nissenson. He was no failure but seems to have often felt himself one. So I am glad to see this tribute. No doubt if he had been more sentimental and less of a truth-teller, he might have had more readers. In this age, it is his glory that he hewed to his own path.

Monday, April 14, 2014

"Irresistible Sonnets" at Lady Word of Mouth

This is a treasure that you must allow to ravish you slowly.

--Robin Williams, Author of Sweet Swan of Avon: Did a Woman Write Shakespeare?

This stunning collection of "Irresistible Sonnets", like a handful of snowflakes, contains no two alike.

--Rayne Allinson, Author of A Monarchy of Letters: Royal Correspondence and English Diplomacy in the Reign of Elizabeth I

Click to purchase +

Click to like

Click to purchase +

Click to like

The patreon experiment...

|

| Vignette by Clive Hicks-Jenkins for Thaliad (Phoenicia Publishing, 2012) |

So far all the material is free, as a good deal of it will be as I go on--now up are the first chapter of A Death at the White Camellia Orphanage, a group of poems from The Foliate Head, and a link to material from Thaliad. I'll probably continue putting out a lot of free material, as I don't see how people can become interested in work without seeing it! In addition, there's a post with link to the great poetry giveaway.

In the near future, the patron-only material will be small short stories, which I have begun writing while proofing galleys for an upcoming book. These (or a group of these) will be posts that ask for a dollar in return, or about a half of a Starbuck's regular brewed coffee. Actually I rarely see a Starbuck's in the hinterlands, so I might be wrong about that one. Also, other work that I want to keep private, either because I'm planning on expanding it or because I want to publish it elsewhere, will be patron-only.

I'm planning on keeping the experiment for at least a month. After that, I'll see what I think and either drop the account or keep going. Writers have to be nimble in times of change, and the world of publishing is certainly in ferment. My hope is that it will be an interesting experiment in finding new readers and ways to support what I write.

Saturday, April 12, 2014

Dear friends and readers of The Palace at 2:00 a.m.,

|

| my current front page image at patreon.com |

http://www.patreon.com/marlyyoumansI'm looking forward to the experiment and hoping that it may help to expand my readership. I will leave a notice here whenever I post something at patreon, whether free or not. Hope you will support me by your presence there!

Good cheer and watch out for dystopian futures,

Marly

P. S. First post: here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)