|

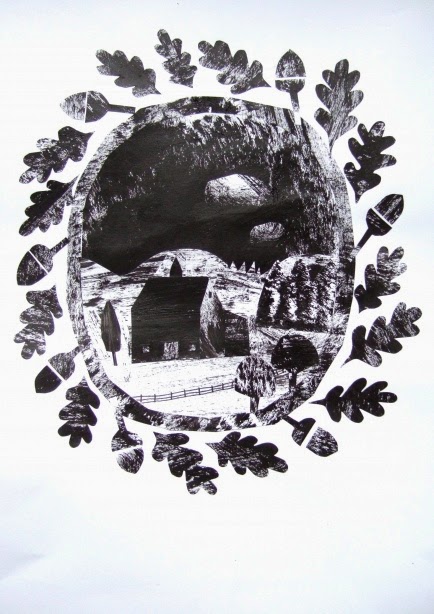

| Interior decoration by Clive Hicks-Jenkins for Glimmerglass, out in September. A lion, a leaf, and a crown--surely they are nothing if not realistic. And yet, put them together... |

Often I'm startled by my own absurd temerity in saying anything about books. What do I know? Why don't I stick to my own narrative and lyric frolics and words and keep my mouth fast shut otherwise? A writer is always making things up, beginning at the very beginning--knowing nothing about how to make what she must make next. It's yet another thing about being a writer that enforces (or should enforce) a kind of humility, whether a writer wants it or not. Having revised a poem or novel or story, I hold an amount of strange knowledge . . . and yet it all flies out the nearest window, never to return, when I sit down with the blank page, the not-yet-born next.

Yet I do persist in this mania of having and changing opinions, thinking that I know things about what I do. For example, I've long felt that the roots of our literature in English are quite other than what is often praised--this thing called realism that so dominates much of our thinking about books. And I've felt, in fact, that there is no such thing as realism, just as there is no such thing as the fantastical or irrealism. These words are but handles, convenient ways of describing points on a continuum. As I've said before, if a book could be perfectly and wholly "realistic," it would then replace reality in one Borgesian swoop. All works of literature are made from nothing, or from Yeats's "a mouthful of air." That is the nature of creation and the sub-creation that is literature.

From Beowulf to Gawain and the Green Knight to The Tempest to Tom Jones to Bleak House to the latest narrative in prose or verse, what matters in poetry and fiction is energy. Is the work alive? And the answer to that question has little to do with where a work falls on the continuum between realist and irrealist, and everything to do with whether it captures something of the energies of life.

* * *

ON RESOLVING TO SHUT UP (AGAIN)

It occurs to me (once again) that I have already said these things before, in some way or another. These morning thoughts, written before the dawn . . . Waking, making. Making is a kind of waking, isn't it? And a maker desires to be awake, to wake others.

* * *

OUR BORING, MODERN OBSESSION

Here's Jacob Bacharach, author of A Bend in the World, at Huffington Post:

Sometimes I think that all the really great works of surrealism predate our boring, modern obsession with dividing the real from the unreal, truth from fiction, the conscious mind from the dream. I'm using surrealism in its common and not specific sense; a lot of the works I'm going to mention are what you might call magical realist, or experimental, or postmodern, or just plain weird. I'm actually a fan of weird fiction myself. If my own writing ever spawns a genre, that's the name I'll lobby for. Anyway, in working on a current unfinished writing project, I've been rereading the Bible, and it's reminded me that of a friend of mine who once said that Revelation was his favorite science fiction novel. I'm a fan of Job, myself, which would give Burroughs a run for his mugwumps, although for true weirdness, you really ought to reread Genesis, in which the utterly ordinary and the utterly otherworldly coexist and commingle in a manner totally alien to the modern ear and imagination; the poetry of creation gives way to genealogy, and God flits between instantiating His word and dickering with little humans over the specific price and measure of disobedience...Via that interesting young seminary professor and writer, Wesley Hill

I tend to think that all great literature has an element of the fantastical and the surreal: Bolaño, Melville, Djuna Barnes, Anne Carson, Laurence Sterne... Each era throws up writers who take their elbows to the way we're supposed to see things, and these are the ones I come back to when I am bored with being bored.