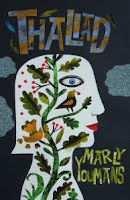

|

| Mary Boxley Bullington, Briar-Patch. 2009.

Acrylic, gesso, oil pastel on paper, 30" x 22."

Julia Rose Collection, Fork Union, VA.

Click for larger images. |

In response to a request to interview some of my painter friends, I have been interviewing Mary Boxley Bullington. As she, in turn, insisted on interviewing me, a part of the You asked series will be composed of our questions to each other.

Bullington:

You are unusual among contemporary American poets in that you love form and formal meter. Why do you love it so much? And how does this help you when you are writing and revising your poems? And how does it help you write free verse?

Youmans:

Dear Mistress Nosey,

Why do I love formal poetry so much? I love shapeliness. I love complicated rhythm and sound, all interwoven and laced and accruing energy as it goes, like a basket full of light. I like the way a sudden contorted idea, say, can be reflected in the meter. Or how the swiftness, sleekness of a running cat is caught in metered lines. Whatever the subject, form can marry content in a great celebration of vigor and sound when the constraints of form are imposed. I love the way poetry lives in the borderlands between the written word and song, and that metrical poetry is always running toward the land of song.

I also love difficulty of achievement, and striving for the goals of mastery—to be better than I am, to grow bigger on the inside as I go. In

The Castle of Indolence, Tom Disch wrote that many a free verse poet would come a cropper if attempting to wield meter and rhyme. As someone who didn’t give up on formal poetry, he no doubt had received a good bit of scorn for his perseverance in the art. But some of our poetry has become entirely too easy—any bit of prose broken into lines can be claimed as a poem. The result can appear very far from the spirited playfulness of creation. Formal poems don’t leave a lot of room for the easy; they’re salutary medicines, good and joyful for the mind.

Do I object to the existence of free verse? Not at all. I write some, now and then. When I write in that mode, I feel free in a way that must mimic this historical movement of poetry—that is, I’m breaking with my own past, frolicking and dancing on the bones of metrical lines. (Here Ms. Mary Boxley Bullington will want examples, but she’ll just have to wait until a batch of newish free verse poems of mine is up online—six will be in

At Length soon. Even there, a reader would see lots of parallelism, sound weaving, narrative, and other organizational strategies.) It’s only when I’ve written a good deal of formal poetry that I think it even possible to write some free verse that satisfies me.

The world of poetry used to be a big place, crammed with many and varied forms, but for a very long time now it has been dominated by short lyric poems, often containing a small epiphany. Writing in form leads a poet to explore forgotten forms, and to discover that poetry once had a far greater range of subject that we find today.

Thaliad (Phoenicia, 2012) is part of a Western epic tradition that includes Homer and Virgil. What other forms have we tended to forget? Bucolics (eclogues). Satire. Masque. Verse epistles. Romance. Georgics. Canticle. Plays in verse. Riddles. Philosophical essays in verse. Etcetera. Allegory probably will never come back, but some other genres might be re-made for our day. I like to live in that larger realm of forms; I like to write my poems inside it. And that means writing in shapes. Sometimes it means thinking about how to make very old things live again and be new.

You ask about revision. Rhyme especially warrants revision. To make every rhyme feel natural and yet have it be plucked from a limited array of words; to have the syntax be clear while yet landing the rhyme syllable(s) at line’s end; to avoid padding to get to line’s end: these are the sorts of challenges that appear when a writer begins experimenting with form. Write in metrical lines for long enough and the making of them may feel like instinct. But it’s perilously easy to make an error, simply by paying attention to rhyme words and not to the context and the poem as a whole. An error in rhyme word choice becomes an error in meaning or tone or logic, and a little time shows those mistakes clearly—more clearly than in a free verse poem, where decisions made often seem fuzzy or random.

Rhyme is magic. Magic! Rhyme whirls the poet to an unexpected place. Rhyme tosses the poet away from any obsessions with the self. It insists that allegiance is not to oneself but to the poem, and to the making of new sense from the swirl of rhyme sounds generated by the opening lines. Thus rhyme demands a certain self-forgetfulness. Self-forgetfulness is a fruitful way to be, if a poem is in the offing. Rhyme sounds hurl the writer toward fresh ideas that never would have appeared if the constraint of rhyme hadn’t pushed a new direction.

Here’s an example from a sonnet where I had no plan, no goal, and only that lovely sense that a poem was about to wash through me; rhyme led the way forward (from

Able Muse, winter 2013; reprinted in

Irresistible Sonnets from Headmistress Press, 2014, edited by poet Mary Meriam):

Waterborne

(from “The Baby and the Bathwater”)

Let it go, let it all go down the drain—

Ash from the crossroads where a witch was burned,

Dirt from the cellar where a queen was slain,

No heir escaping death, and nothing learned,

The crescent moons of darkness under nails,

Ditch-digger’s drops of sweat, the blood from soil

That sprouted fingertips, the slick from snails

Glinting on butchered peasants left to spoil:

Let it swirl, let it all swirl down the drain—

Let murderous grime be curlicues to gyre

Around the blackened mouth, let mortal bane

Be gulped, and waste be drink for bole and briar.

Here’s a new washed babe; marvel what man mars,

The flesh so innocent it gleams like stars.

I’m not all that fond of walking people through poems—I prefer unmediated experience—so I’ll just say something about the progression in the poem as it related to rhyme. And this I am only doing because Mary asked, so don't expect it to happen again! Going for “learned” as a rhyme with "burned" tilted the poem strongly toward the hopelessness of history and experience (whether witch-burnings, the Russian Revolution, the Holocaust, etc.) as a means to teach human beings and so reinforced the idea of “letting it go.” (Yes, it's a rather dark poem.) “The crescent moons of darkness under nails” pointed a way toward other dark and light elements in the poem—stars, the round black mouth, the silvery track of snails. (Seen from the right angle, recurrence of such opposing images is a kind of rhyme as well.)

Though it’s a Shakespearean sonnet, the poem tends to break in half after the first two quatrains that are a catalogue of darknesses. The opening line of the third quatrain is almost a repeat and uses the same end-word as the first line, and that means an increased tightness in the rhyme scheme. The voice in the poem is more commanding, thanks to repetition and parallelism, and it also rises to a higher pitch of speech, moving considerably away from daily talk. (A great deal of contemporary free verse is allergic to a higher level of speech.) “Drain” calls up a rhyme word out of the past, out of the real but half-mythic world where witches are burned and queens murdered: “mortal bane.” “Gyre,” likewise, is a higher note, and “Let murderous grime be curlicues to gyre” is probably the line that surprised me most. “Gyre” generated a word connected with the mythic realm of witch-spelled, sleeping queens: "briar."

The turn in the final couplet to the baby, a newness salvaged from the bathwater of history—whether an everyman sort of baby or even the Christ child, marred by man—was in great part generated by sound. “Marvels” led to “mars,” and “mars” in turn led (for no planetary reason!) straight to stars. As a mother, I was often struck by the fairy beauty of babies and small children. I never fully knew that beauty until I had children of my own. My small, blond children sometimes seemed to reflect light, to glisten and be gleaming with tiny crystals. So the very opposite of marred man and woman was unmarred infancy, bright and clear, unsullied by the darkness of history. In the end, the poem doesn't throw out the baby with the bathwater.

In poetry, rhyme makes us make it new. Rhyme makes me surprise myself, and surprise in creation is a delightful, invigorating feeling that urges a writer on. The poet then follows a magical thread from rhyme sound to rhyme sound, calling up new and unexpected meanings. Rhyme is the smack of the ball hitting the bat and flying into the sun—coming down and caught who knows where.

|

| Early Snow, January 2016

Acrylic, gesso, India ink, oil pastel on paper,

22" x 22." |

I notice that you have decided that I am a New Formalist. You may like to know that, in fact, I did not know the term until a few years ago, about the time Kim Bridgford invited me to be on a panel and later to run a panel at the West Chester Poetry Conference. Even now, I am not entirely sure what New Formalism is, other that a list of those poets who are willing to write in meter and sometimes rhyme. I occasionally go by Eratosphere to see what some of those people are doing and who has a new book. Somehow I don't think that's enough to make me a member of a literary movement.

I notice that you have decided that I am a New Formalist. You may like to know that, in fact, I did not know the term until a few years ago, about the time Kim Bridgford invited me to be on a panel and later to run a panel at the West Chester Poetry Conference. Even now, I am not entirely sure what New Formalism is, other that a list of those poets who are willing to write in meter and sometimes rhyme. I occasionally go by Eratosphere to see what some of those people are doing and who has a new book. Somehow I don't think that's enough to make me a member of a literary movement.  And I would not dare to claim a part in any movement, as I completely failed in my duty to live in large cities and know poets. In fact, I lived for a very long time without knowing many poets--I seemed to know mostly fiction writers and painters. Now I know more, thanks to twitter and Facebook and such places, but I can't say that I have restricted my knowledge to writers who like meter and rhyme.

And I would not dare to claim a part in any movement, as I completely failed in my duty to live in large cities and know poets. In fact, I lived for a very long time without knowing many poets--I seemed to know mostly fiction writers and painters. Now I know more, thanks to twitter and Facebook and such places, but I can't say that I have restricted my knowledge to writers who like meter and rhyme.