|

| Order by March 20 for a discounted price-- one for yourself, some for friends! http://www.phoeniciapublishing.com/the-buddha-wonders.html |

92 pgs, 6" x 9", paperback,

publication date March 18, 2018

Preorder price $13.50 US (reg $14.95)

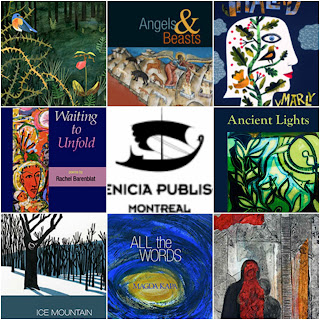

Phoenicia Publishing (Montreal) has announced the forthcoming publication of Luisa Igloria's next book. I'm glad the news is out and, as I feel warmly toward both the publisher, Elizabeth Adams, and the poet herself, I am doing my little bit toward letting the world know.

Many of the 53 Buddha poems have appeared in initial form at Dave Bonta's Via Negativa site; the versions below are from that site. The book is her second with Phoenicia, and follows her 2014 publications, Night Willow (Phoenicia) and Ode to the Heart Smaller Than a Pencil Eraser, chosen by Mark Doty for the 2014 May Swenson Prize (Utah State University Press.)

While you're at Phoenicia (go!), sign up for the Phoenicia newsletter and take a look at the catalogue, the related art prints, and music. The publisher: "Please Sign Up to receive news and exclusive special offers, 4-6 times per year, via email. In March, two subscribers will win a free copy of "The Buddha Wonders..." in a random drawing among our mailing list members."

The Buddha fills in job applications

Luisa A. Igloria March 28, 2014

Almond the shape of my eyes; lotus

the width of my hips or the soft

inscrutability of a half-smile.

Virtue the act of sitting still,

going nowhere, being a stick-in-

the-mud. Or being pliable: sucking

the tummy in, filling it out with breath

or bread. Give me the bread, the bowl

of milk, honey from the hive, water

from the well, wine from the skin

that loosens all tongues and turns

every fool into a resident sage.

The Buddha listens

Luisa A. Igloria March 24, 2014

in the kitchen to a classical program

on the radio, one evening while cold rain pelts

the window before turning into pellets of ice—

And he thinks Mendelssohn’s Octet in E flat

Major, Op. 20 is the perfect soundtrack for this

moment— the violins and their upbow so quickly

spanning and gathering a range of feeling

he did not know still simmered under his skin.

Where did they come from: that flare of resentment,

that thorn of anger, the ache of loneliness

from a love he yearned for but could not have?

How is it possible to cultivate detachment

at the same time that one practices compassion?

He rinses his cup and saucer and sets them

on the rack to dry, his fingers lingering

in midair as if to trace the notes

that exit in the scherzo.

Dear Naga Buddha,

Luisa A. Igloria November 10, 2012

how still, how still you sit

beneath the ticking of the seven-

headed tree; it’s hard to understand,

but just like ours, those tongues

have foraged along the ground

for leftovers, for milky drops

of immortality. O careless and

forgetful gods, you’ve crowned us

with accidents, spiked our appetites,

littered the way with detours

and false starts. No warnings issued

about sharp blades of grass that split

the ligaments in the mouth: and thus,

in dreams, the restless body turns

and hisses, even in brief repose.

Part for the whole

Luisa A. Igloria September 24, 2016

For my birthday, my friend gave me

the stone head of a Buddha

brought back from her travels

to Nepal and India. My first,

she said, wrapping it in yards

of bubble wrap then hefting all

25 pounds of it into a box.

At home, I found a place for it

in one corner of the deck, next to

the patio set and green canvas umbrella.

Setting shallow terracotta pots of herbs

around it, I wondered where it once held

court: if it sat in a bamboo grove or nameless

village temple, its carved fingers curled,

touching. Its eyes don’t give anything away.

It doesn’t say what blasted the rest

of its anatomy, what saved it from complete

ruin in order for the soft bloom of green

to spread like the shadow of a milkweed

butterfly across the high cheekbones.

|

| Luisa Igloria |