|

| Maddy Aldis-Evans photograph, Exeter Cathedral, Somerset |

For me, a better way to question foliate heads is to begin by assuming that they belong where they are. Then the question becomes why they belong in a church setting, and how that reason could make sense to a medieval Christian.

I've always felt that these odd heads were not surprising, and I thought about it again last Saturday when hearing my friend James Krueger (Mons Nubifer Sanctus) say that God creates freely and so can make a free creation that is itself free to create and be fruitful--as it says in Genesis, "let the earth put forth" and "let the waters bring forth."

|

| The Foliate Head UK: Stanza Press, 2012 Green man by Clive Hicks-Jenkins |

|

| Maddy Aldis-Evans photograph, water spout, Kelmarsh St. Denys, Northamptonshire |

If the foliate head precedes Christianity in Europe (a thing we do not know one way or another), there's certainly a reason why it followed men and women into churches and cathedrals; the generative, bringing-forth head must have fit the transformed world. And if it did not precede Christianity, the head must have seemed a good thing to bring into a changed world for the first time. Either way, it appeared somehow right to a medieval Christian to sculpt a greening face. Likewise, the image must have met the approval of priests and architects.

A green head is at one with the purposes of the God as revealed in Genesis, fulfilling the injunction of fruitfulness. Mouth (or sometimes nose) breathes out leaves, breathes out the spirit of creation. The head that puts forth leafy breath is usually male, sometimes a woman, sometimes a creature, sometimes a crowned king. Thanks again to James for the reminder that "spirit" and "breath" are the same word in Hebrew and Greek, and for the thought that the late-created human being in Genesis is a microcosm of creation, combining and holding earth ("dust") and intellect and spirit as one.

This idea of a person as microcosm is a lens through which we can approach the foliate head even more clearly. "I am a little world made cunningly," says Donne, years later but in harmony with his medieval forebears and the Genesis story. How does the idea of microcosm as lens work, and why might a medieval Christian find a foliate head perfectly congenial with the words heard on the Sabbath? First, in a green man or woman we find the image of God, for Genesis tells us that each human being is made in God's image. Each person (green or not) is also, then, a kind of microcosm of God. Second, God in turn is known through the Creation. Each human being is also a microcosm of Creation, created from dust, mind, and breath of life. As a result, each person has the potential of reflecting back God's nature and Creation. In that way, a man or woman may become creative and fruitful (like the foliate head), living in harmony with the purposes of God.

But these are very strange portrayals of human beings. What might a head sprouting leaves have said to a medieval Christian about life lived as a reflection of God and Creation? I suggest that it might have told the observer to live a larger life that was more expansive, more creative, and more like God. That's a lot to ask of anybody, much less a medieval peasant. Yet such an urging is a natural outgrowth from the power displayed by foliate heads. These green images from churches and cathedrals are full of energy, sometimes almost lost in a thicket-sphere of leaves. They are wildly alive, vital and strong. Nothing is stinted. Everything flourishes. All these statements would have worked for a medieval Christian as ways of describing the powers of God and Creation. From an alien yet human head--the microcosmic image of world and God--a torrent of free creation bursts forth, spilling with leafy, lavish Niagaras of new life. The foliate head says in its green speech, then and now, go and be like me.

|

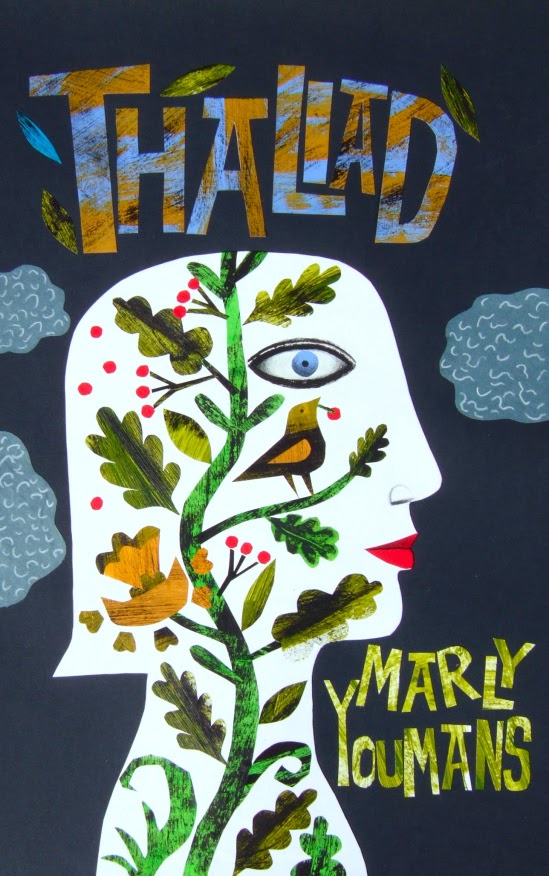

| A foliate Thalia (art by Clive Hicks-Jenkins) |

|

| Clive Hicks-Jenkins, green man from The Foliate Head. |

So, when I go about town with a cabbage leaf on my head (hidden under my ballcap) as I almost always do, especially in warm weather, am I being strangely religious in some way?

ReplyDeleteDo you? How wonderful. I didn't think people did things like that anymore...

DeleteI expect that the head has to green on the inside as well as the outside, Tim. If you show signs of that, yes!

I used to use aluminum foil under hat, but that was only to deflect the errant radio signals that were digging their way into my brain (courtesy of NSA and other black-ops units). I am much better now!

ReplyDeleteI expect aluminum foil had the disadvantage of being hot in the summer down South.

DeleteLet me know when the leaves start crawling out of your ears!

what a discovery! i'm agog! maybe it would help me - does the brand of tin foil make any difference?

DeleteI don't know why you went to spam today! But I expect you should try several different brands...

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete"A green head is at one with the purposes of the God as revealed in Genesis, fulfilling the injunction of fruitfulness."

ReplyDeleteI realize I'm about to type some rather absurd reductionisms, but I blame that on this little FB box and the fact that it's been about a decade since I researched this topic and so don't have the scholarly articles and original source material at hand. Also, please note any criticism of Christians (or pagans) is directed at specific offenders, not everyone, not even most.

But two things struck me with this sentence, aside from the fact that there will probably be many people startled by it: Back in the medieval day, there did not seem to be such a huge chasm between people and the natural world, so to express nature in the religious was a given. [I have almost a degree in English linguistics, but I can't recall what Middle English for "herp a derp" might be.]

Modern day "Dominionism" wherein God calls His people to rape and pillage the Earth in the name of capitalism (whether to bring about the End Times or just 'cuz), and a good dose of anti-science fundamentalism have driven a wedge between liberal-commie environmental unwashed hippies and the righteous. This has sadly left a lot of earth-loving folks, whatever their politics or religious affiliation, to see Christianity and nature loving as inimical. As someone who has done time both in the fundamentalist Christian and pagan worlds, I have seen the animosity both sides have for each other. There were naysayers at our church-run school who didn't think we kids should go camping because we might decide to "worship the Creation over the Creator." And I could regale you with tales of pagan fundamentalism, too, which helped me to see the agnostic I really am.

And my second thought: There was also a time in the history of Christianity when what we now call "the occult," and many of those things that form the sacraments if you will of many of today's neo-pagan practices, were actually "Christian mysteries." Several of the most famous of grimoires were penned by Christians, even if they may have been considered heretics. A.E. Waite in more recent times created the most widely used Tarot deck and was deeply involved in esoteric/occult groups but still considered himself a Christian. Some of the pillars of the modern Wiccan/pagan scene wrote spellbooks using the Psalms.

It both fascinates and repels me that there's this tendency now to need to sort the world along such stark lines, and even worse, to inflict this view upon the past.

A very interesting response.

DeleteYour comments reminded me that this morning after skimming around on the internet, I tweeted this : "Startling how much voice illogical and loveless people have in our culture..." Certainly in my lifetime we have moved toward a position where all sorts of groups and subgroups (not just the ones you mention) have zero interest in understanding one another and a great deal of hostility toward one another. Political groups in particular are resolute about their dislike and scorn for others. It is a curious time to be a writer, when the population is fragmented and isolated and many people don't really want to understand people unlike themselves. Reading is down, and reading is one of the few arenas where many people can feel understanding and affection for others who are not like themselves. The bad effects of this trend definitely spill into nature vs. human beings issues. Also into much more...

I've been very interested in the literary uses of that intersection between Christianity and alchemy in the matter of striving for the philosopher's stone accompanied by soul transformation into a kind of "gold," but don't know so much about the other things you mention, though I've used some tarot images in "The Book of the Red King." But though I knew the images, I didn't know anything much about Waite, though I assumed a connection with theosophy. Curious. I will have to look up a little bio of the man.

I expect that if people didn't continuously return to first principles for reformation, a religion would quickly become very different from its roots. And the history of that sort of back-and-forth is fascinating and often strange. I'm reading a book about exegesis (biblical and literary) that begins by tracing the history of how people saw scripture, and how we ended up with "the few academics who pay attention to Scripture have kept themselves busy ripping the Bible to pieces, skeptically analyzing its factual claims, mocking the idiocy of the final redactors, criticizing its ethical teachings, and generally treating the Bible with contempt even while protesting their piety. A book whose very letters Jews and Christians once treated with reverence has been reduced to a heap of broken fragments" (Leithart, "Deep Exegesis.) Anyway, I'm still reading the historical portion (up to Kant now) and finding historical transformations of thought to be interesting. So it reminded me of what you say. I've been asked to read it and visit a study group (where I will presumably be the person who understands poetry!) of rectors and pastors. Should be a challenge.

When people ask, "Why would medieval Christians put grotesques and pagan symbols on their buildings?", I'm inclined to suspect that they're too biased by the relative austerity of certain prominent types of modern Christianity to discern how florid, fluid, and imaginative medieval Christianity often was.

ReplyDeleteI'm currently translating a pile of medieval poems about farming, gardening, and nature, and Janet, I think, is right: Nature and religion were so intertwined in the Middle Ages that I can't imagine Christians *not* easily finding ways to use and interpret the green man. They might very well have been baffled by the modern notion that they should have shunned or repudiated such a big, useful symbol of fecundity.

Ah, Jeff, the medieval-mad one--so glad you came by! Janet will like that comment...

DeleteMany people in our time have a conviction that people in past times were "just like us." And that idea leads to misreadings (and also to novels set in the past with 20th/21st century characters playing dress-up.)

I was just reading about Kant and the Bible--Kant stripping the husk and leaving the bare kernel of idea that relates to natural religion. It reminds me of your comment about the florid, imaginative medieval world. We have stripped the husk from many things...

We have abolished all the sense of a green world "putting forth" because creation is called to be free and fruitful by a God who is creative. I'm not sure fecundity and Christianity can go together without that emphasis.

I hope you'll be publishing those translations, by the by...

Here is my simple-minded, unsophisticated comment regarding medieval folk and Christianity: Christianity, especially as redesigned over the years by the Roman Catholic church became and remains medieval in form and spirit. The Renaissance and Reformation and the Age of Reason somewhat altered Christianity, but its medieval form remains most intriguing and influential. Early Christians (prior to Augustine) would hardly recognize Christianity in either its medieval or modern forms.

ReplyDeleteYou know, that is such an enormous set of claims that I can't begin to grapple with it. So I will just say something very bookish in response.

DeleteThat means I'll have to say something about the Bible, which is the main book we have in mind here. The meaning of the words of that book have been in flux over the years--the apostles had very particular ways of reading and understanding that were lost or rejected over time. The medieval world had the fourfold method or quadirga as a guide. And now I've just been reading Leithart about Meyer and Spinoza and others, ending with Kant and his contemporary inheritors. Leithart (to simplify) argues that many critics over many years tore away meaning, choosing as they wished and ignoring that the book comes to us "in a particular form, using particular categories, introducing a particular language." But Leithart follows E. D. Hirsch in advocating a stable verbal meaning and rejecting relativism.

So from one point of view, we could say that there is something changeless in the church, and that is scripture. If some through idea choose to veer away from the text and a close look at original sources and carefully-translated language, well, that does not change the book, which would be recognized in various "thens" and now.

Of course, now I'm moving on to the part of the book where Leithart deals with hermeneutical techniques of the apostles, which looks to be pretty wild... And will be a challenge to "stable" text because for them, the Old Testament firmly predicts the new.

I'm going to have to write something about Leithart, I suppose, because going to visit the rectors' study group should be a rather different experience. Evidently a lot of the rest of the book ("Deep Exegesis") refers to poetry, and so I am going along as the token poet... Should be unusual.

And of course there is much else that is "changeless" beyond the text, for a person of faith. It's the changeless things that matter.

DeletePerhaps somebody brave and long-winded will tackle the extent of your comment!

Re: "First, in a green man or woman we find the image of God, for Genesis tells us that each human being is made in God's image. Each person (green or not) is also, then, a kind of microcosm of God. Second, God in turn is known through the Creation. Each human being is also a microcosm of Creation, created from dust, mind, and breath of life. As a result, each person has the potential of reflecting back God's nature and Creation. In that way, a man or woman may become creative and fruitful (like the foliate head), living in harmony with the purposes of God."

Delete'Twas Augustine who plunged us into a centuries-long meditation upon what it meant to be made in the image of God. For him, it was clear that the human soul, not the body, was the made in the imago Dei. And while the imago (our souls) could be stained and disfigured--vandalized, if you will--by our sins, it could not be expunged, and thus remained as the ground of grace within us (De trinatate). In this scheme, the human memory enabled even the most corrupt human soul to turn back to God. Medieval exegesis and even particular monastic movements took for granted that human memory--and particularly scriptural memory--could become the ground for conversion.

The keystone of both ancient and medieval biblical exegesis was verbal and imagistic concordance between scriptural passages, especially scriptural passages belonging to the Old Testament when brought into concordance with passages from the New. Perhaps the most common medieval trope for memory was the digestive system. (I am forever indebted to Mary Carruthers for her writings on the medieval memorial culture and its metaphors.) Medieval writers did not invent new stuff; rather, after grazing among the little flowers of many books, they memorized and digested what they read in their hearts (memorial digestive anatomy is a bit weird) and then regurgitated a "single honey" made from these many disparate pollens.

In this sense,the image of the green man or woman breathing or spewing out leaves may directly link to the function biblical memory in changing and restoring the human soul to God's image. (In my dissertation, I argued that the Pearl-poet takes th digestive memorial metaphors so for granted in his poems that he burlesques it in his retelling of the story of Jonah, who is first digested and spewed up by the whale, then by a "wodebynde"--a honeysuckle or, in my reading a wode/ crazy bynde/vine or entanglement. Hilariously, Jonah doesn't recognize the memorial trope that has swallowed him whole--or the meaning of God's message to the Ninvites that he has spewed all over town. (He wanted them to be swallered down by the earth, but instead those rotten Ninevites repented. How dare they!)

Anyway, I love Marly's idea that the green man and woman carvings in churches spewing out foliage might represent the fulfillment or regeneration of the human soul. It could also suggest the restorative, salvatory preachments of the clergy, who certainly understood from early on the importance of turning pagan imagery to their own uses.

Mary, that is wild! I love the digestive memory business... I like this whole thing, especially Jonah and the woodbine. Enjoyed very much.

DeleteI wish somebody would do a book about the changing relation of soul-body-mind from classical thought through the medieval and Renaissance periods. The idea that they can be separated out--where does that start?

oh, damn--there was a scholar in the late 80s--early 90's who became famous for her research on min-body in the Middle Ages. Somebody help. The memory function in my imago dei is pretty stained and damaged!

DeleteThink Columbia Univerity and saints' lives, embryos and cannibalism in medieval dialectic.

mind-body, I meant. Phooey!

DeleteEureka! Caroline Walker Bynum. See http://www.amazon.com/Holy-Feast-Fast-Significance-Historicism/dp/0520063295/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1395415583&sr=1-2&keywords=holy+anorexia

DeleteHere's a hot link to the book Mary recommended.

DeleteMy "enormous set of claims" -- seeming to get the same kind of reaction as an old man's flatulence in the adjacent church pew -- grows out of my readings of history o'er the years and -- more particularly books by Elaine Pagels, Stephen Greenblatt's Hamlet in Purgatory, and accounts of the rise and fall of the Roman Catholic church in medieval and early modern England. If my off-handed, off the top of my head comments have caused too much of a stink, I apologize. I think my mind does not operate at the more sophisticated and better educated levels you are suggesting in your rebuttal/comment; I think I would have been a perfect medieval peasant -- not much profound thought happening there either.

ReplyDeleteIndeed, no. You mistake me! It's a perfectly fine set of remarks, but I did not feel equipped to come to terms with that comment. "Rack me not to such vast extent," as Herbert says!

DeleteI did share something I am reading that related, but I never, ever would feel so about a comment--would never suggest that you were either gassy or without something to say that was worthwhile. I simply didn't feel able to respond that huge extent of time, though perhaps somebody else who happens along will be.

Besides, for me to behave as you imagine I might would be . . . discourteous to someone in my little e-house! You are always welcome.

Clive is smiling!

ReplyDeleteI knew that!

DeleteHad an interesting note from Timothy Hoover as well--all green man fans are smiling (unless they are stuck on a different theory, I suppose.)

we've got one in the back yard, on one of our trails...

DeleteNow are you talking about a wodwo who hangs out in the trees, or are you talking about an image? (I prefer to be gullible and hope it is the former.)

DeleteFacebook comments on the foliate head post...

ReplyDeleteFascinating and erudite discussion that I do not feel qualified to enter, but I will gladly lurk.

ReplyDeletePut leaves in your hair and dance about in the trees!

DeleteWodwo! Wodwoman!

Delete