|

| Maddy Aldis-Evans photograph, Exeter Cathedral, Somerset |

For me, a better way to question foliate heads is to begin by assuming that they belong where they are. Then the question becomes why they belong in a church setting, and how that reason could make sense to a medieval Christian.

I've always felt that these odd heads were not surprising, and I thought about it again last Saturday when hearing my friend James Krueger (Mons Nubifer Sanctus) say that God creates freely and so can make a free creation that is itself free to create and be fruitful--as it says in Genesis, "let the earth put forth" and "let the waters bring forth."

|

| The Foliate Head UK: Stanza Press, 2012 Green man by Clive Hicks-Jenkins |

|

| Maddy Aldis-Evans photograph, water spout, Kelmarsh St. Denys, Northamptonshire |

If the foliate head precedes Christianity in Europe (a thing we do not know one way or another), there's certainly a reason why it followed men and women into churches and cathedrals; the generative, bringing-forth head must have fit the transformed world. And if it did not precede Christianity, the head must have seemed a good thing to bring into a changed world for the first time. Either way, it appeared somehow right to a medieval Christian to sculpt a greening face. Likewise, the image must have met the approval of priests and architects.

A green head is at one with the purposes of the God as revealed in Genesis, fulfilling the injunction of fruitfulness. Mouth (or sometimes nose) breathes out leaves, breathes out the spirit of creation. The head that puts forth leafy breath is usually male, sometimes a woman, sometimes a creature, sometimes a crowned king. Thanks again to James for the reminder that "spirit" and "breath" are the same word in Hebrew and Greek, and for the thought that the late-created human being in Genesis is a microcosm of creation, combining and holding earth ("dust") and intellect and spirit as one.

This idea of a person as microcosm is a lens through which we can approach the foliate head even more clearly. "I am a little world made cunningly," says Donne, years later but in harmony with his medieval forebears and the Genesis story. How does the idea of microcosm as lens work, and why might a medieval Christian find a foliate head perfectly congenial with the words heard on the Sabbath? First, in a green man or woman we find the image of God, for Genesis tells us that each human being is made in God's image. Each person (green or not) is also, then, a kind of microcosm of God. Second, God in turn is known through the Creation. Each human being is also a microcosm of Creation, created from dust, mind, and breath of life. As a result, each person has the potential of reflecting back God's nature and Creation. In that way, a man or woman may become creative and fruitful (like the foliate head), living in harmony with the purposes of God.

But these are very strange portrayals of human beings. What might a head sprouting leaves have said to a medieval Christian about life lived as a reflection of God and Creation? I suggest that it might have told the observer to live a larger life that was more expansive, more creative, and more like God. That's a lot to ask of anybody, much less a medieval peasant. Yet such an urging is a natural outgrowth from the power displayed by foliate heads. These green images from churches and cathedrals are full of energy, sometimes almost lost in a thicket-sphere of leaves. They are wildly alive, vital and strong. Nothing is stinted. Everything flourishes. All these statements would have worked for a medieval Christian as ways of describing the powers of God and Creation. From an alien yet human head--the microcosmic image of world and God--a torrent of free creation bursts forth, spilling with leafy, lavish Niagaras of new life. The foliate head says in its green speech, then and now, go and be like me.

* * *

Green man collaborations: Clive Hicks-Jenkins

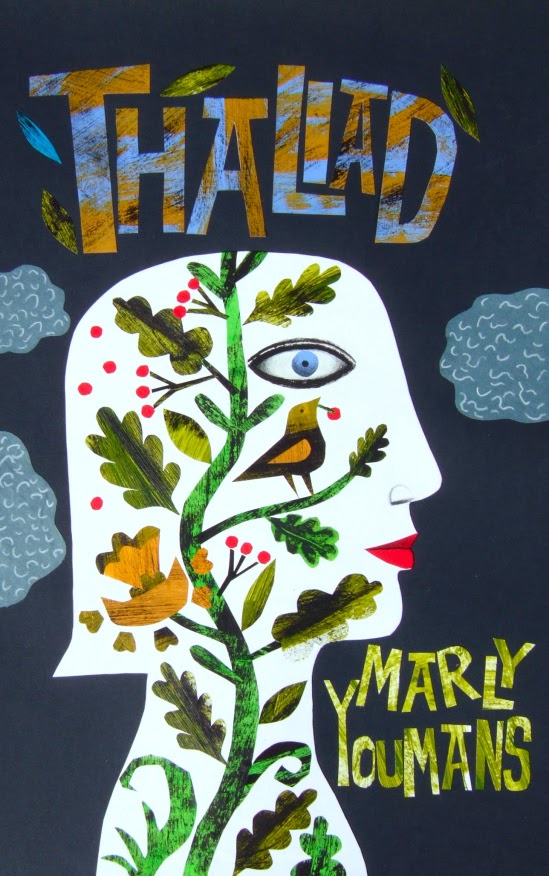

Marly and I are friends that have long shared an interest in this subject, and so it was only ever going to be a matter of time before we collaborated on a 'foliate' project. In fact come to think of it, the first book we did together, her novel of twindom and life in a forest, Val/Orson, also had an underlying 'foliate' theme, and so did our last, her epic narrative poem Thaliad. You'll find that in time that no matter how deeply you mine them, the best subjects return over and over again to inspire. --Clive Hicks-Jenkins to Timothy Hoover, who is exploring the ways of the green man in mask-like constructions made form natural materials

|

| A foliate Thalia (art by Clive Hicks-Jenkins) |

|

| Clive Hicks-Jenkins, green man from The Foliate Head. |